Units-and-measurements Cheat Sheet

Vectors in 2D and 3D

A vector

Component Form

- 2D:

- 3D:

Magnitude of a Vector

- 2D:

- 3D:

Unit Vector

A unit vector

Vector Addition and Subtraction

If

- Addition:

- Subtraction:

Graphically, vector addition follows the parallelogram or triangle rule.

Scalar (Dot) Product

Here,

- If

, then and are perpendicular (unless one is a null vector).

Vector (Cross) Product (3D only)

Magnitude:

- If

, then and are parallel (unless one is a null vector). -

-

-

Position, Displacement, Velocity, and Acceleration

Position Vector

Describes the location of an object in space from the origin.

Displacement Vector

Change in position from an initial point

Average Velocity

Instantaneous Velocity

The time derivative of the position vector.

Speed is the magnitude of the velocity vector:

Average Acceleration

Instantaneous Acceleration

The time derivative of the velocity vector (second derivative of position).

Motion with Constant Acceleration

If

Equations of motion can be applied independently to each component.

Equations of motion can be applied independently to each component.

- Velocity:

- Position:

Where

Component-wise Equations (2D example)

| X-component | Y-component |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Projectile Motion

Motion of an object under gravity only (neglecting air resistance).

- Acceleration:

(assuming y-axis is vertical upwards) -

Initial velocity:

Where

Where

Equations of Motion

-

(constant) -

-

-

Key Formulas (assuming

- Time to Max Height

- Maximum Height

- Time of Flight (

): For landing at - Horizontal Range

: For landing at - Trajectory Equation:

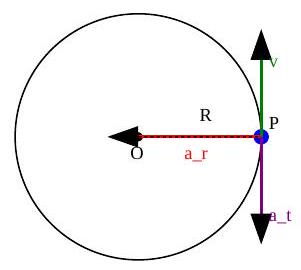

Uniform Circular Motion (UCM)

Motion in a circle at constant speed

- Radius of circle:

- Angular speed:

(radians/second) - Period:

(time for one revolution) - Frequency:

Centripetal Acceleration (

Directed towards the center of the circle, changes the direction of velocity, not its magnitude.

In vector form:

Centripetal Force (

The net force causing centripetal acceleration.

Non-Uniform Circular Motion

Speed is not constant, so there is both tangential and radial acceleration.

- Tangential Acceleration

: Changes the speed of the object. It's parallel or anti-parallel to the velocity vector.

- Radial (Centripetal) Acceleration (

): Changes the direction of the object. Directed towards the center.

- Total Acceleration (a): Vector sum of tangential and radial accelerations.

Relative Motion

Velocity of object A relative to object B :

Velocity of object B relative to object A :

If

General relative velocity equation:

General relative velocity equation:

Where

Example: Boat in a River

-

: velocity of Boat relative to Water -

: velocity of Water relative to Ground (river current) -

: velocity of Boat relative to Ground

Example: Airplane with Wind

-

: velocity of Airplane relative to Air -

: velocity of Air (wind) relative to Ground -

: velocity of Airplane relative to Ground

Newton's Laws of Motion

Newton's First Law (Law of Inertia)

An object at rest stays at rest, and an object in motion stays in motion with the same speed and in the same direction unless acted upon by an unbalanced force.

Newton's Second Law

The acceleration of an object is directly proportional to the net force acting on it and inversely proportional to its mass. The direction of the acceleration is in the direction of the net force.

Where

Newton's Third Law

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. If object A exerts a force

Common Forces

Weight (

Force of gravity exerted by a planet on an object.

Where

Normal Force (

The force exerted by a surface perpendicular to the surface, preventing an object from passing through it.

Example: For an object on a horizontal surface,

Example: For an object on a horizontal surface,

Tension (

The force transmitted through a string, rope, cable, or wire when it is pulled tight by forces acting from opposite ends.

Friction Force (

Force that opposes relative motion or attempted motion between surfaces in contact.

- Static Friction (

): Opposes impending motion. It adjusts its magnitude up to a maximum value.

- Kinetic Friction (

): Opposes actual motion. It is generally constant once motion starts.

Where

Spring Force (Hooke's Law)

The force exerted by an ideal spring, proportional to its displacement from equilibrium.

Where

Applications of Newton's Laws

Free-Body Diagrams (FBDs)

A diagram showing all external forces acting on an object. Essential for solving force problems.

- Isolate the object(s) of interest.

- Draw all forces acting on the object (not forces exerted by the object).

- Choose a coordinate system.

- Resolve forces into components.

- Apply Newton's Second Law (

).

Connected Objects

Treat each object separately with its own FBD. Identify common forces (e.g., tension in a string, normal force between contacting surfaces) and common accelerations.

Atwood Machine

Two masses connected by a string over a pulley.

Assumptions: massless string, massless and frictionless pulley.

Assumptions: massless string, massless and frictionless pulley.

Inclined Plane

Object on a ramp. Resolve gravity into components parallel and perpendicular to the incline.

- Perpendicular component:

(balanced by normal force) - Parallel component:

(causes motion down the incline)

Work, Energy, and Power

Work Done by a Constant Force

Where

Work Done by a Variable Force (1D)

Work Done by a Variable Force (1D)

Kinetic Energy (

Energy due to motion.

Work-Energy Theorem

The net work done on an object equals the change in its kinetic energy.

Gravitational Potential Energy (

Energy due to an object's position in a gravitational field.

Where

Elastic Potential Energy (

Energy stored in a spring or elastic material.

Where

Conservative Forces

Forces for which the work done is independent of the path taken (e.g., gravity, spring force). Associated with potential energy.

Non-Conservative Forces

Forces for which the work done depends on the path taken (e.g., friction, air resistance). Dissipate mechanical energy.

Conservation of Mechanical Energy

If only conservative forces do work, total mechanical energy (

Conservation of Energy with Non-Conservative Forces

If non-conservative forces like friction are present, they do work (

Power (

The rate at which work is done or energy is transferred.

Units: Watts (W), where

Momentum and Collisions

Linear Momentum (

A vector quantity, product of mass and velocity.

Units:

Impulse (

Change in momentum. It's the integral of force over time.

For a constant force:

Impulse-Momentum Theorem

The impulse acting on an object equals the change in its momentum.

Conservation of Linear Momentum

If the net external force on a system of objects is zero, the total linear momentum of the system remains constant.

For a two-body collision:

Types of Collisions

- Elastic Collisions: Both momentum and kinetic energy are conserved.

- Inelastic Collisions: Momentum is conserved, but kinetic energy is NOT conserved (some is lost to heat, sound, deformation).

- Perfectly Inelastic Collisions: Momentum is conserved, objects stick together after collision (

). Maximum possible kinetic energy loss.

Coefficient of Restitution

A measure of the elasticity of a collision (1D).

-

for perfectly elastic collisions. -

for perfectly inelastic collisions. -

for inelastic collisions.

Center of Mass (CM)

The average position of all the mass in a system.

For discrete masses:

For discrete masses:

Velocity of CM:

The total momentum of a system is equal to the total mass times the velocity of its center of mass.

If

If

Rotational Motion

Angular Position (

Measured in radians, angle from a reference line.

Angular Displacement (

Change in angular position.

Angular Velocity (

Rate of change of angular position.

Units: rad/s.

Angular Acceleration (

Rate of change of angular velocity.

Units:

Rotational Kinematics (Constant Angular Acceleration)

Tangential and Angular Quantities Relationship

For a point at radius

- Arc length:

- Tangential speed:

- Tangential acceleration:

Note: These apply when

Moment of Inertia (I)

Rotational equivalent of mass. Measures resistance to angular acceleration.

For a point mass

For a system of discrete masses:

For continuous mass distribution:

For a point mass

For a system of discrete masses:

For continuous mass distribution:

Parallel-Axis Theorem

Used to find moment of inertia about an axis parallel to one through the center of mass.

Where

Rotational Kinetic Energy (

Torque (

Rotational equivalent of force. Causes angular acceleration.

Magnitude:

Newton's Second Law for Rotation

Work Done by Torque

For constant torque:

Rotational Power

Angular Momentum (

Rotational equivalent of linear momentum.

For a point particle:

Magnitude:

For a point particle:

Magnitude:

Conservation of Angular Momentum

If the net external torque on a system is zero, the total angular momentum of the system remains constant.

For a rigid body:

Gravitation

Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation

Attractive force between any two objects with mass.

Where

Gravitational Field Strength

Acceleration due to gravity at a distance

On Earth's surface,

Gravitational Potential Energy (

For two masses

Escape Speed (

Minimum speed an object needs to escape the gravitational pull of a celestial body.

Where

Orbital Speed (

Speed required for a stable circular orbit at radius

Kepler's Laws of Planetary Motion

- Law of Orbits: All planets move in elliptical orbits with the Sun at one focus.

- Law of Areas: A line that connects a planet to the Sun sweeps out equal areas in equal times. This is a consequence of conservation of angular momentum.

- Law of Periods: The square of the orbital period (

) of a planet is proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit. For circular orbits, .

Simple Harmonic Motion (SHM)

Periodic motion where the restoring force is directly proportional to the displacement from equilibrium and acts in the opposite direction.

Key Parameters

- Amplitude (

): Maximum displacement from equilibrium. - Period (T): Time for one complete oscillation.

- Frequency (

): Number of oscillations per unit time. . - Angular Frequency

.

Position, Velocity, Acceleration (for

- Position:

- Velocity:

- Acceleration:

Mass-Spring System

Angular frequency:

Period:

Simple Pendulum

For small angles

Angular frequency:

Angular frequency:

Period:

Where

Energy in SHM

Total mechanical energy (

At maximum displacement (

At equilibrium

Thus,

At equilibrium

Thus,